In 1990, the Pillsbury Doughboy, Pillsbury’s beloved brand mascot, was transitioning away from stop-motion animation to CGI animation. But animator Tom Rubalcava, who was hired at Colossal Pictures the same year to work in their animation department, had no way of knowing he would work on some of the Doughboy’s final stop-motion commercials.

It seemed particularly strange to think most commercials, starring brand mascots or otherwise, would eventually be produced in CGI. Stop-motion animation was becoming mainstream in feature films again. A few years prior, Rubalcava had produced 99 animated episodes of the “Gumby Adventures” TV series starring Gumby, the surrealist green humanoid character made of clay who was famously animated in stop-motion. After the blockbuster success of “Jurassic Park,” CGI would become all the rage.

What was it like to work during one of animation’s greatest shifts? Rubalcava takes PopIcon behind the scenes of animating one of Poppin’ Fresh’s final stop-motion campaigns.

From Making Short 8mm Films to Animating Gumby

For Tom Rubalcava, school was all about art. He excelled in art classes and as early as his teen years had an interest in filmmaking and animation. Inspired by sci-fi and Ray Harryhausen films, Rubalcava would make short 8mm films with his neighborhood friends.

After graduating from high school, Rubalcava would meet like-minded filmmakers and start working as a crew member in local independent projects. While in community college in Diablo Valley, Concord, California, Rubalcava took courses in film history and TV production alongside longtime friend Dan Morgan. Morgan and Rubalcava had previously experimented with prosthetic makeup in their 8mm films when they were younger. After being assigned to work on a short film together, they decided their project would be a mini documentary on “Planet of the Apes” makeup effects. They entered their documentary in the school’s film festival and won second place in documentary shorts.

Then came Rubalcava’s big break. In the audience at the student festival was a young film director whose first feature film was to be funded by Roman Coppola, the son of film director Francis Ford Coppola. He approached Rubalcava and Morgan, asking if they would be interested in creating makeup for his feature film debut and the pair said yes.

However, as time for preproduction got closer, Rubalcava realized he was more interested in art director and storyboarding. Even though he had sculpting skills with makeup, Rubalcava was itching to get back to 2D art. As Rubalcava recalls, the director and producer saw his portfolio of storyboards and concept designs and placed him to work in an art direction role on the film.

Not long after the film’s completion, a colleague from an earlier independent film let Rubalcava know Art Clokey, creator of Gumby, was resurrecting the character and its stop-motion animated series. They were hiring at Premavision Studios in Sausalito, California. In 1987, Rubalcava was hired to work on Gumby and found himself back in his sculpting roots in the character fabrication department.

From 1987 to 1988, Rubalcava would produce 99 animated episodes for the “Gumby Adventures” TV series. He stayed on to work on “Gumby: The Movie” which would later be released in 1995. As Rubalcava started to look for more work as a freelancer, he found out about Colossal Pictures.

The Quiet Intensity of Animating a Stop-Motion Pillsbury Doughboy Commercial

Watch the reel above for a glimpse into the mighty world of Colossal Pictures, an entertainment company which developed and produced TV programming, ads, visual effects, and more.

Rubalcava, who was hired at Colossal Pictures to help fabricate a Ritz Bits Peanut Butter Sandwiches commercial, found his freelance work experience quickly took off. Norm DeCarlo, a fellow puppet maker on the “Gumby Adventures” show, contacted Rubalcava about working on some Pillsbury Doughboy TV commercials.

Rubalcava was familiar with the Doughboy and excited to work on the campaign, especially since the Pillsbury Doughboy started off as a stop-motion animated brand mascot.

“As a youngster, researching what I could about Ray Harryhausen, many other iconic stop-motion animated characters were presented to me, including King Kong, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” characters in George Pal’s Puppetoons and even from foreign creations from countries including Czechoslovakia, Russia, and Germany. I sought out as much information as I could about stop-motion which was available in print or on VHS before the advent of the internet,” said Rubalcava.

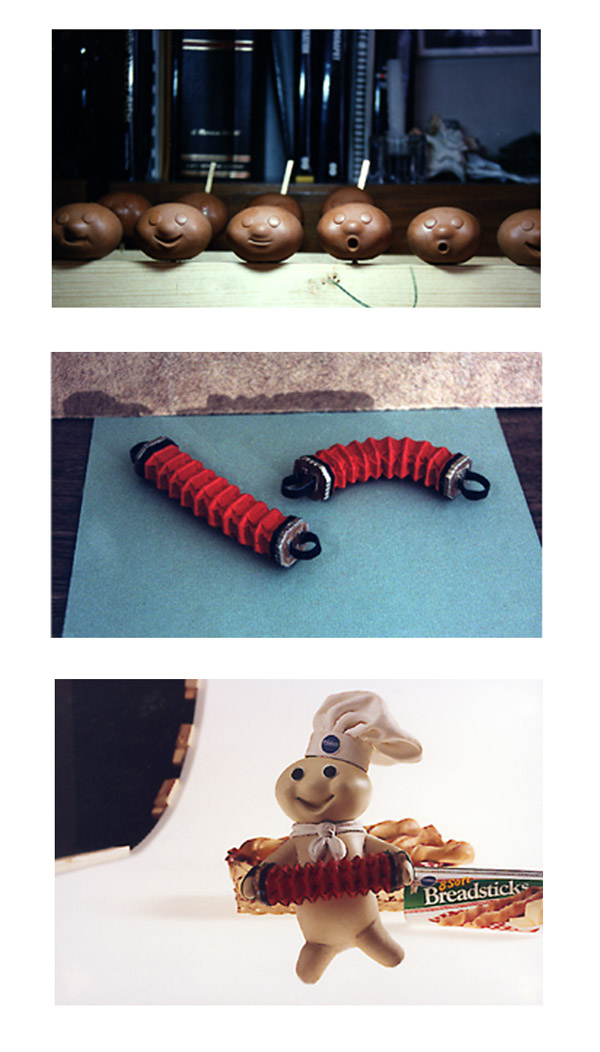

The Pillsbury Doughboy in a stop-motion animation capacity used figure bodies which were ball and socket armatures. Animators had to position his wrist, arm, and shoulder so he could move around. Holes were drilled into the surfaces of the floors he stood on. The Doughboy’s feet were unscrewed in and out for walking scenes and a painted rod was attached to his back to help hold him upright.

Rubalcava recalls the ball and socket armatures for this campaign were designed and machined by Tom St. Amand, a stop-motion veteran who had previously worked on “Star Wars.” The Doughboy’s armatures were fitted with tapped threads on the bottom of the feet. One could use wing nut bolts to secure the puppet to the floor from under the set. In addition to the painted rod attached to the Doughboy’s back keeping the character stable between steps while walking, the rod could be raised and lowered frame by frame if an action such as a leap or jump was called for the character.

Positioning the puppet, Rubalcava said, was achieved by using surface gauges. These are metal pointers attached to a small metal platform and adjustable enough to follow whatever limb was to be moved. After each incremental frame of movement, the animator would place the gauge near the puppet. The pointer would almost touch the puppet, marking the last position. Then, the puppet would be moved slightly away from the pointer for the next position. The gauge would then be removed from the shot and the exposure taken. This process would be repeated to help the animator keep track of the direction movement and how far to move the puppet or its extremities.

If this sounds a bit time consuming, it’s because it is. Stop-motion animation takes a lot of time. Using this methodology would only allow animators to produce several seconds per day for a campaign. In addition to the laborious amount of time it takes to animate in stop-motion, Rubalcava said the animators hoped the shots turned out as planned.

Rubalcava only visited the set periodically for the Doughboy’s stop-motion animation. Usually this meant if there was a puppet repair needed or a prop to deliver. The on-set atmosphere was quiet, even tense at times, as everyone concentrated on getting the few seconds of animation needed each day. If the Doughboy puppet suffered armature issues, such as a ball and socket joint loosening and being unable to hold its position properly, Rubalcava would conduct minor puppet surgery. A slit would be cut into the foam body to tighten a hex screw and then carefully glued back together.

Props also played a key role in the Doughboy’s commercials throughout the 1990s. The character needed props for every individual spot. Every prop was different and Rubalcava had a hand in the entire 1990s campaign since the puppet fabrication work he helped with was present in each of these ads. In a commercial for Pillsbury Soft Breadsticks, the Doughboy plays a concertina made by Rubalcava just for Poppin’ Fresh.

Changes to the Doughboy’s Tummy Tickles

What made working on a Doughboy stop-motion commercial in 1990 different than previous decades was achieving the infamous stomach poke.

Ever since he made his commercial debut, the Pillsbury Doughboy has always laughed when poked in the tummy. For decades, a molded hand prop would come in a frame at a time and actually touch the puppet’s stomach during animation. In the 1990s campaign, Rubalcava said the tummy tickle was done using a rod animated in to touch the Doughboy’s tummy. Later in post-production, an actor’s hand was shot against green screen and comped in over the rod.

Should Brand Mascots Receive the Stop-Motion Animation Treatment Again?

Rubalcava would eventually be hired full-time at Colossal Pictures and join their animation department in 1991. He worked on many 2D animated TV spots from cereal commercials starring Cap’n Crunch to being on loan to the CP fabrication shop to assist on other stop-motion projects such as Hershey’s Kisses and Nabisco’s Chips Ahoy campaigns.

Does Rubalcava believe stop-motion animation can make a comeback? Absolutely. Bringing Poppin’ Fresh back to his primitive roots might be the nostalgia the world needs right now.

“I think anytime there’s opportunity to create something in stop-motion it is well worth it. CGI is great and the advancements made are remarkable, but there’s timelessness and charm of stop-motion animation which captures the imagination,” said Rubalcava. “I think bringing Poppin’ Fresh back to his ‘primitive’ roots would give us all a warm and cozy feeling.”

The CGI (latter day) doughboy was at best annoying. The stop motion figure definitely showed the character and hard work that went in to producing the commercial. Bring back the stop motion doughboy so I don’t have to go on fantasizing maiming the CGI figure.